| Adult barnacles are sessile, and require a suitable area of substratum to which each individual can become permanently attached. The act of settlement by a barnacle cyprid larva determines the final location of the adult. The widely dispersed cyprids become reaggregated on suitable substrata, and cyprids select the most advantageous position in relation to other barnacles. After settlement and metamorphosis, each juvenile barnacle must acquire by diametric growth an area in its inmediate vicinity sufficiently large to meet its adult requirements. Those species with isolated or sparse populations may have no problems in doing so; but many species live in dense populations, and competition for space can then be intense. | |||

Cyprids are capable of swimming and of crawling over hard substrata, but these forms of locomotion are too inefficient to either return them to substrata bearing their parents or to ensure the discovery of other suitable substrata on which they can settle. Only wind and tide driven water currents are capable of transporting them over the necessary distances. However, cyprid behaviour in both the swimming and exploratory crawling phases can concentrate the spatfall on suitable substrata.

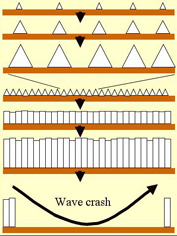

In the swimming phase, upward movement concentrate cyprids near the water surface. This ensures encounters with intertidal substrata given onshore winds, but offshore winds would result in the cyprids being blown out to the open ocean. However, many intertidal species tend to settle during the warmer month of the year when onshore sea breezes during the day would reward photopositive swimming.

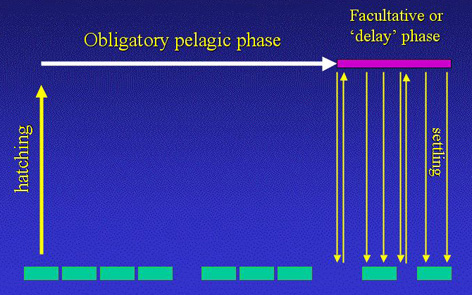

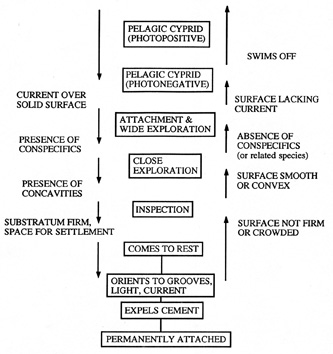

Sooner or later, a swimming cyprid comes into contact with a solid substratum. When this occurs, a new phase of behaviour is initiated involving, in sequence, attachment by the antennules, exploration through walking on the antennules, and fixation by the antennules. if, during exploration, the substratum proved unsuitable, the cyprid swim off. However, the cyprid is a non-feeding stage and it would be non-adaptive to swim away from a substratum when the probability of living long enough to fine another more suitable one was low. Thus cyprids are expected to become less likely to swim off substrata with increasing age.

Exploration takes place in two phases. The first is a wide searching performed by steady walking across the substratum, with few changes of direction. If suitable conditions are detected, the behaviour changes to close searching (the second phase), with frequent changes of direction. This may lead to concentration on a very restricted area, followed by fixation. Numerous factors are known to influence the settlement of barnacle cyprids. They are summarised in the table below (also see the figure above 'Behavioural cascade').

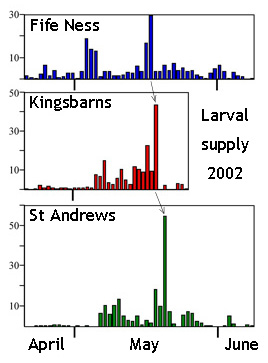

At high settlement levels post-settlement processes seemingly are the primary determinant of adult density.

|

Cues

|

Responses and other remarks

|

| Light | Photopositive or photonegative. |

| Flow regime | Degree of disturbance of the water, current over solid surface. |

| Orientation of substratum | The sueface texture and topography of the substratum. |

| Microbial biofilms | Barnacles condition the environment suitable for the microbes necessary for barnacles to survive. Different barnacle species respond to different combinations of bacteria and their expolymers. |

| Future predators | Barnacles detect the cue throught the deposition of mucus on available substrata. The effect maybe stimulatory or inhibitory (cnidarians, limpets, predatory whelks, algae). |

| Dominant space competitors (the presence of adults of the conspecifics) |

Chemical signals, rapid settlement. Some chemical cues stimulate settlement, others are inhibitory. Adverse effects of high settlement densities on suitable substrata may be alleviated by 'territoriality' (spacing-out behaviour). |

| Prey organisms |

The presence of other barnacles in the immediate vicinity of the final settlement position of a cyprid could clearly interfere with its future growth. This is particularly true in the shore Balanomorpha, which often settle in very dense spatfall which may grow to cover all the available space on the substratum. In such species, and in some sublittoral forms, settling cyprids space out from previously settled barnacles on the substratum.

Cyprids of S. balanoides, B. crenatus and E. modestus, spaced out from each other at settlement. Each settled cyprid or metamorphosed spat was found to have a 'territory' around it in which later arrivals were very unlikely to settle. The size of this territorial separation was little greater than the sum of the radius of the previously settled spat and the length of the settling cyprid, i.e. something of the order of 1-2 mm.